Director, cinematography, editing, special effects, and music: Aaron Dylan Kearns

Actor: Aaron Dylan Kearns

Genre: Experimental

Runtime: 11:59

Budget: $0

Release Date: August 29, 2017

Production of this short started in November of 2016. At the time, we were in a Midtown Atlanta apartment building, one in which I had grown up, living there for 13 years.

This is a personal film, and how it is personal is the reason I became interested in the gentrification problem that is destroying settled urban communities and forcing out lower income populations with luxury development that makes in-town living only affordable for a certain class of individuals, erasing diversity of class from such areas.

When I was four going on five, we were gentrified out of a kind of art colony (musicians, artists, writers, sculptors) in a diverse area of Decatur, essentially Atlanta. With the move, my mother had chosen the Midtown building as a home for a variety of reasons. The building was diverse, in a diverse neighborhood, with a lot of foot traffic of international students, and my mother wanted me to grow up in a diverse situation. It was ecologically friendly in that it was on a MARTA bus line and just a few blocks from the subway. It was close to my father's music studio (he could even walk there if needed). An art store was within walking distance and my mother reasoned when I was older I would be making use of that (which I did). We were just a couple of walking distance blocks from a grocery store and pharmacy, and we were within walking distance of the High Museum. Because I was already, as a child, wholly involved in art, my mother reasoned if this continued that the High Museum would be a good place to live within walking distance of, because she was hoping that by the time I was older the High might have art programs in which I could be involved. Also, the neighborhood was class diverse, for though there were middle class and upper class buildings and homes all around, our building was one among several others that were still similarly affordable in that area, in a rental market that was forcing artists out of in-town neighborhoods. It was not a “luxury” building. Instead, it was one that offered affordable living in an urban situation (which means it was rundown and needed repairs). There were a number of tenants who had been there many years, and these tenants who were long-term residents when we moved in were still there when we were finally gentrified out.

This was our home--a place where I grew up knowing the landlord and the building's super for 13 years.

A reason, too, the building was affordable was that it was in an area that was not yet fully gentrified. The Pine Street homeless shelter, the largest in the city, was two blocks away on one side. On the other side, two blocks away, was the largest soup kitchen in the city. So, I grew up also in a situation where I was familiarized with the problem of homelessness, and mentally ill people living on the streets. They are people who dropped through the cracks, who society just wanted to keep pushing further and further away into the shadows.

Curiously enough, my mother had appropriately planned in her selection of the building. She had hoped the High Museum would have programs that would benefit me, and that we would be there until I was out of my high school years. When I was in high school and seriously starting to do works in film, the High Museum for two years hosted a film festival for teens and associated film programs for teens, and I was able to walk there from our home and take advantage of these. And as soon as I was out of my high school years, the landlord sold the building and it was gentrified.

When Emory built the Proton Therapy Center a couple of blocks away, it then seemed pretty certain the homeless shelter would be closed down, its presence having staved off development, and gentrification would soon overtake the whole of our area.

Our landlord sold the building, which he and his family had owned since the fifties or sixties, and he said he felt good that the new owners wouldn't tear down the building but would refurbish it and everyone would be able to stay as tenants. The new owners sent us notices that there would be no changes and they looked forward to serving us. Trees and limbs were felled around the building, which made the back inaccessible. Repairs on the roof began. These things were a nuisance but livable. Then, after several months, the residents began getting staggered 90 day notices. Almost immediately our section of the building lost hot water (we were promised it would be fixed but this never happened), leaks damaged our apartment and threatened our computers when water poured through the ceiling, as bitterly cold weather set in the heat was turned on for one week and then turned off for the remainder of November and December. Everyone in our section of the building was suddenly told they had to vacate as water would be cut off completely in two weeks. At the same time, the internet lines were cut, which made it difficult to look for a new apartment.

The building had problems and needed repairs, but this story is still one of gentrification that empties neighborhoods of long resident populations, and the manner in which gentrification occurs so that buildings are made uninhabitable long before one's notice has run out.

What happens is, in order to keep pulling in rental income, tenants are told that they won't be affected by changes. Then when they got their notices, in order to push them out quickly, even while they are still paying rent, the living situation is made so impossible as to be dangerous.

Two years after we were gentrified out, we would be gentrified out of the apartment complex to which we had moved. At that time, the Midtown building we'd been gentrified out of would begin leasing furnished apartments, probably for short term rentals, that go for as much as $4500 a month, which in 2019 is $1500 a month over what comparable apartments rent for in Midtown. Emory has purchased the Pine Street homeless shelter, which was closed down. The homeless have spread into other areas looking for shelter.

As a young teen, interested in artistic expression and going into film, the neighborhood that was my home was already the place and subject of several of my short films. When I realized moving out of the building was imminent, production for this film was begun as a sort of representation of the alienation we all felt when forced from our homes, and our community. It was my personal goodbye as well as a commentary on a larger problem that affects our cities. Some of the footage was taken the day we moved out and the day after, the building by then looking like a veritable war zone, by then almost unrecognizable as the home we had once known.

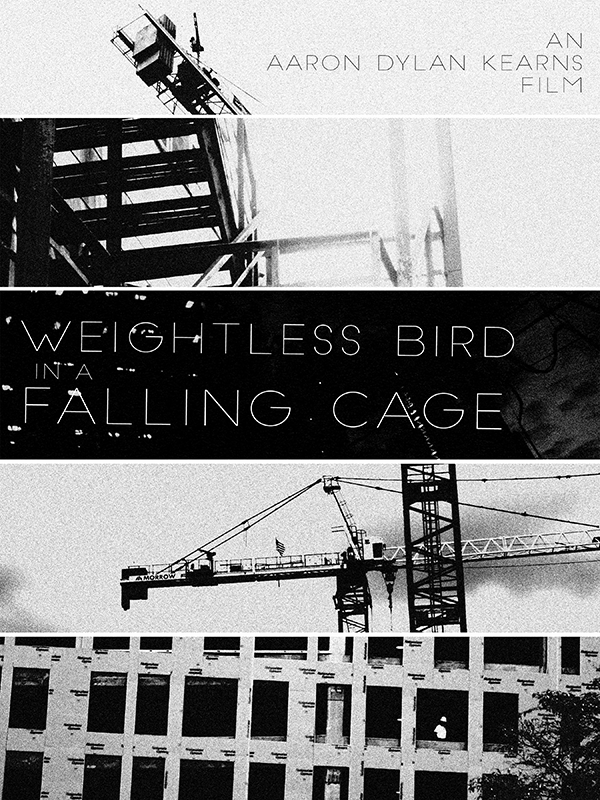

In Weightless Bird in a Falling Cage, a faceless protagonist, in a similar situation, witnesses his home being overtaken by development. The forces behind it are demanding him to leave, destroying his environment, but also consequently push him further and further into his now not-home.

The trailer:

The poster: